The Return of the Nineteenth-Century Presidential Election

Twentieth-Century Elections Were Tame Compared with the Races of the Nineteenth and Twenty-First

From William McKinley to Bill Clinton – the American presidential elections of the twentieth century – results tended to be decisive. Winners didn’t break a sweat; losers got annihilated. The average margin of victory in the popular vote was 12.4 points. Four winners – Warren Harding in 1920, Franklin Roosevelt in 1936, Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and Richard Nixon in 1972 – received more than 60 percent of the popular vote. Harding’s 1920 triumph was the century’s biggest blowout, 26.2 points.

The six elections so far in the twenty-first century have been much closer. The average popular vote margin has been 3.4 points. The largest margin – Barack Obama’s 7.2-point win in 2008 – is barely half the average margin from the last century. No candidate has won more than 52.9 percent of the popular vote. Half of the twenty-first-century elections have been so close that the result remained in doubt until well after election day or the winner did not gain the largest proportion of the popular vote – or both. The twentieth century did not have any of these anomalous results.

The history of American presidential elections in the last twenty years has been defined not by continuity with the recent past but by a reversion to the elections of the nineteenth century.

Nineteenth-century elections were close. The average popular vote margin was 6.5 points. The biggest blowout was seventeen points: Andrew Jackson’s victory in 1832. The maximum proportion of the popular vote was 56 percent – also Jackson, this time in 1828.

The nineteenth century also featured four elections as strange as 2000, 2016, and 2020.

The first was 1800. At that time, the majority of presidential electors were not chosen by popular vote, so there are no nationwide popular vote figures. It was plain in the immediate aftermath of the election that sitting president John Adams, a Federalist, was out and that he would be replaced by a member of the Republican Party (not the same party as today’s Republicans), but it was not clear which Republican it would be. At the time, the top electoral vote getter became president and the runner-up vice-president. The Republicans meant for Thomas Jefferson to be president and Aaron Burr vice-president, but the two tied. When no candidate wins a majority in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives decides the election, with each state receiving one vote.

Once the House started voting, it became apparent this election had no quick fix. Federalists would have a big hand in deciding which member of the rival party would win because eight of the sixteen House delegations were Federalist and two had equal numbers of Federalists and Republicans. In February 1801, the House voted thirty-five times and tied each time. Reaching Inauguration Day, March 4, with no winner became a real possiblity. Governors prepared their militias, and the danger of mob violence mounted. Finally, after receiving what they believed was a promise – it was, in fact, just a prediction – that Jefferson would leave many of their policies in place, several Federalists abstained from voting, throwing the election to Jefferson on February 17.

American leaders soon went to work on ensuring that the debacle of 1800 could never be repeated. The Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1804, prevents a party’s presidential and vice-presidential candidates from getting tangled up again by requiring the electors to vote for the president and vice-president separately.

The first time the candidate who won the popular vote did not win the election was 1824 – the first election for which there is national popular vote data. By then, eighteen of twenty-four states chose their candidate by popular vote, while six let the state legislature decide. Andrew Jackson won 43.1 percent of the popular vote, dwarfing his next-closest competitor, John Quincy Adams, who won only 30.5 percent. But since winning the presidency requires a majority of the Electoral College votes, that margin meant nothing. In 1824, the 262 electoral votes were scattered among four candidates. Jackson won only ninety-nine of them, so this race, too, went to the House. Henry Clay, one of the four contenders, threw his support to Adams, allowing Adams to win enough states to secure the election. Then he named Clay his secretary of state, a position that in those days often eventually vaulted a man into the White House. Many Jackson supporters cried that Adams offered the plum cabinet position for Clay’s support in a “corrupt bargain” – though few historians believe there was a quid pro quo. Jackson drowned his sorrows by winning the next two elections.

In the twenty-first century, Republicans sometimes win the electoral vote while losing the popular vote because they dominate in many sparsely populated areas while getting crushed in a few densely populated cities. In the late nineteenth century, the modern Republicans, the party of Abraham Lincoln, also twice won the electoral vote while losing the popular vote. This happened because the Republicans had very little support in the South, especially because of legal discrimination and intimidation against blacks, who tended to vote Republican. Between 1880 and 1916, Republicans did not win a single former Confederate state. Meanwhile, the two parties were competitive in the rest of the country. Republicans could win enough states to claim the Electoral College, but their huge losses in the South sometimes prevented them from winning the popular vote.

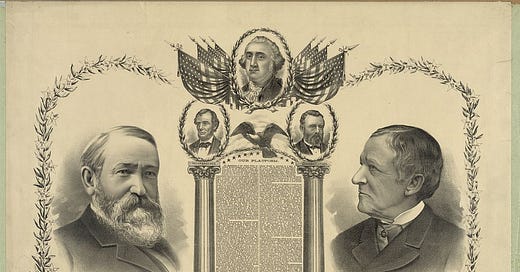

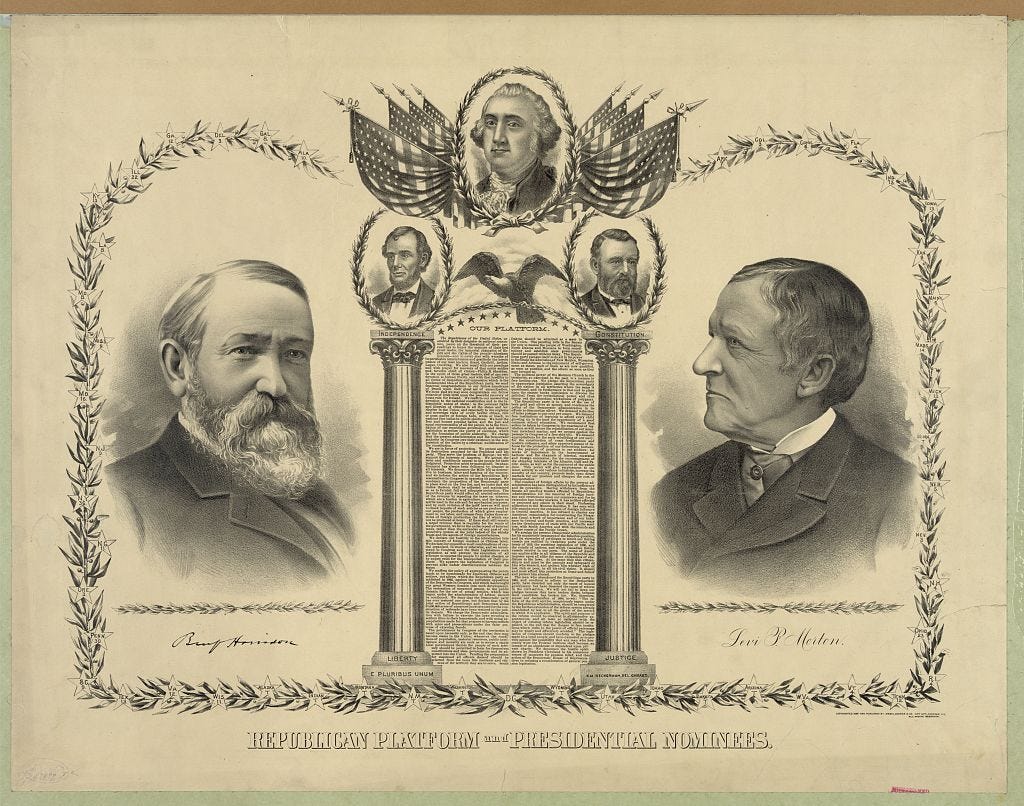

In 1888, Republican Benjamin Harrison won despite losing the popular vote by seven-tenths of a point. He lost every Southern state, often by wide margins, going down by thirty-nine in Texas, forty-two in Georgia, forty-seven in Louisiana, forty-eight in Mississippi, and sixty-five in South Carolina. He won every state outside the South, but those victories tended to be narrower.

The other time nineteenth-century Republicans won despite losing the popular vote, 1876, was more dramatic. Rutherford Hayes lost the popular vote by three points to Democrat Samuel Tilden, partly because of losses of twenty to forty-four points in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Texas. The result was disputed in Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana, but “returning boards” ruled that Hayes won them all. Hayes was able to win there largely because United States troops were still stationed in the South protecting black and Republican voters as part of post-Civil War Reconstruction. Those Southern victories gave Hayes a one-vote majority in the Electoral College, but then Democrats managed to have one Oregon electoral vote ruled illegitimate, creating a tie. The Federal Electoral Commission nevertheless ruled Hayes the winner. Congress next had to certify the election. Democrats held the House of Representatives and agreed to give Hayes the victory only if Republicans would remove United States troops from the South, ending Reconstruction. Republicans agreed, and Hayes won perhaps the most debatable election in American history.

The coming weeks may be unpleasant for Americans, but, if they are, nineteenth-century elections at least show that wacky results are far from unprecedented.

Thanks. Very informative and readable and timely. I'm sharing with others.