Why Nations Collapse: Warning Signs from Strange Defeat

Between 1914 and 1918, France demonstrated its strength. It withstood German invasion until Germany wilted. Then, with its allies, it imposed a punitive peace.

In May 1940, France again faced a German invasion. This time, it fell in forty-four days.

How could a once-powerful nation be so utterly stampeded?

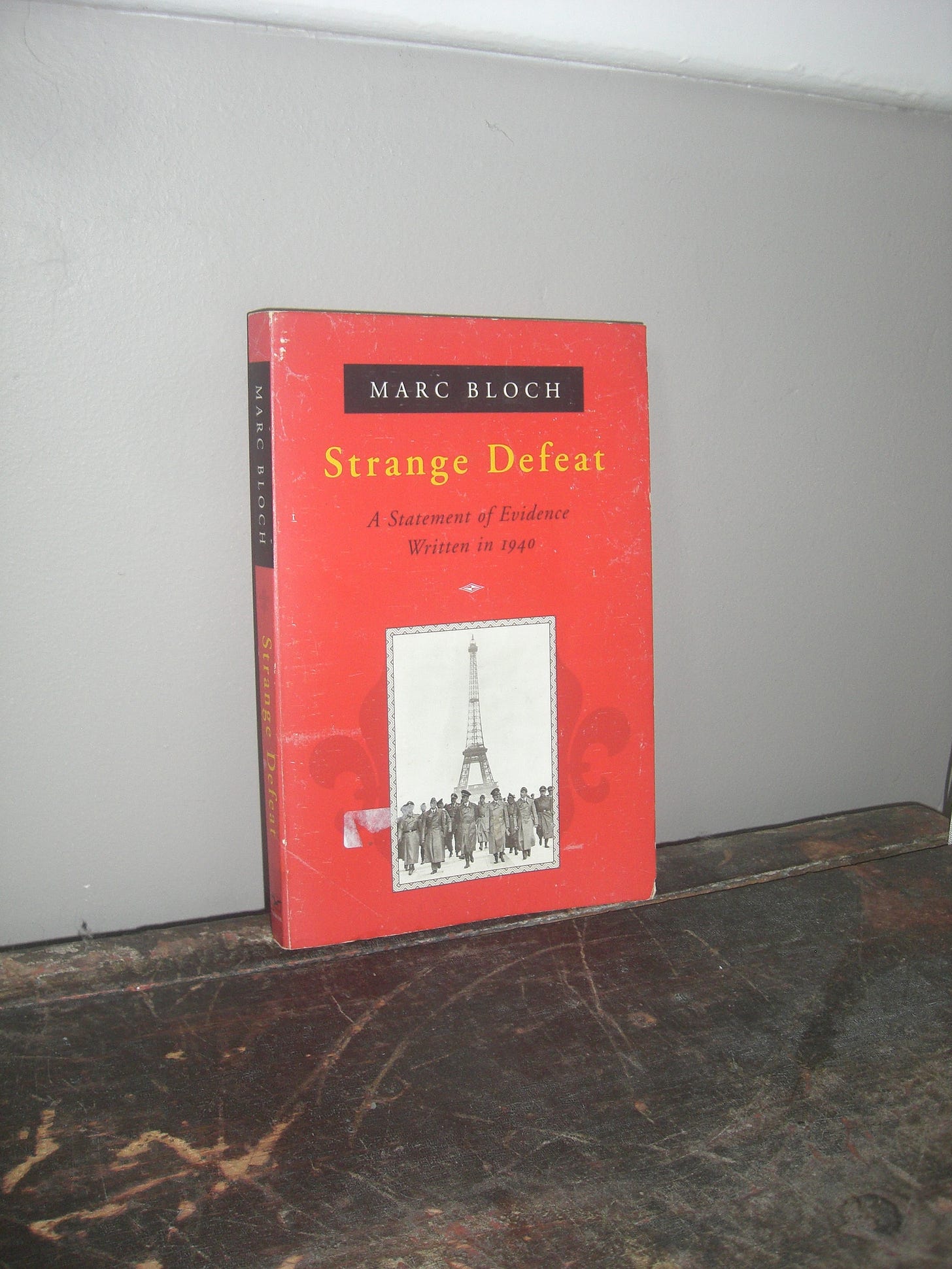

Tormented by what he saw as “the most terrible collapse in all the long story of our national life,” Marc Bloch spent the following months writing an explanation. He drew on his experience in the French army during the war, additional research, and the insights he had gained during a productive career as a historian. In 1949, five years after he was executed by the Gestapo for helping the French Resistance, his study was published in English as Strange Defeat: A Statement of Evidence Written in 1940.

Although Bloch did not try to generalize beyond France, his work offers warning signs of when an apparently strong nation is likely to cave under pressure.

Bloch saw national disintegration comprehensively. Military weakness played a significant role. Bloch attacked “the utter incompetence of the High Command,” referring to the staff officers and highest ranking field officers. But he followed the roots of defeat deeper than breakdown on the battlefield by revealing how it was also the fault of the whole civilian population.

Military failures

1. Education: Miseducation of officers stultified the army. War games did not account for the complexity and unpredictability of a real war, such as how hot meals would benefit morale. Many of its officers had taught in officer training school, a practice that hardened them against new ideas. Students of these officers learned to apply theory to war, not how to adjust to the unexpected – but “the Germans refused to play the game according to Staff-College rules.” Officer training also corrupted the army with “the faulty teaching of history.” Instead of being showed how historical change tends to happen, students simply learned that the present would resemble the past, namely the First World War that the teachers experienced. Compounding the problem, students who parroted their teachers won higher rank than those who did not.

2. Adjustment: Officer training prepared France well – for re-fighting the First World War. But by 1940, war was much more based on motorized vehicles and aircraft than it had been a generation earlier. Officers’ predictions of what the war of the future would be like were wrong. They thought fortifications would make them invulnerable, artillery would be more effective than aircraft, and mechanized warfare would be slow, night-based, and dominated by the defenders. Consequently, the French invested too little in mobile weaponry, kept encountering German forces where they did not expect them, failed to prepare for the damage dive bombers did to morale, and tried to regroup too close to the front lines. France not only relied too much on fortifications but planned them badly. The Maginot Line covered only the German border, leaving a weak spot along the Belgian frontier on its left flank that German forces exploited. The “concrete block-houses” that the French did place along the Belgian border were built to withstand an attack from the east – but the decisive blow against them came from the west. Making matters worse, officers did not adjust once the true nature of the war became apparent.

3. Culture: France’s military culture did not keep its forces prime for battle. The quality of officers of all ranks deteriorated during the decades after the First World War. Although far too many were old, a policy enacted in the late 1930s made it more difficult for young men to win promotion. Peacetime military experience such as keeping up with reams of routine paperwork deadened wartime instincts. The culture of paperwork also made it too cumbersome to fire ineffective officers. These influences produced officers who were complacent, unwilling to change, and unable to take initiative and make quick decisions. There were other problems. Officers damaged morale by behaving in a domineering way toward their men. Generals competed with one another. Many members of the high command broke down under pressure. A major contributor was a practice of steeping themselves “in a perpetual atmosphere of fuss” featuring “too little sleep, hasty meals, and the lack of proper routine.” French officers refused “to think things out quietly” although “unhurried planning alone could have saved us.”

4. Execution: France’s military fizzled in action. Its system of equipping new recruits, ability to communicate, and intelligence gathering were all ineffective. The complexity of the army’s organizational structure contributed to the army’s poor communication, and it dampened officers’ willingness to take responsibility. France and its ally Great Britain did not coordinate well.

Civilian failures

1. Fear: The French were “timid souls.” Hoping to save lives and prevent a repetition of the destruction of the First World War, French leaders chose not to defend cities with populations above 20,000. Civilians fled over minor threats. Many men of prime fighting age tried to win cushy positions that would keep them out of combat, such as billets at the Ministry of Munitions. Instead of exercising “ruthless heroism” the government tried to save lives by exempting many young men and older boys from military service.

2. Division: France was riven by class conflict in the decades before the war. Workers were growing more militant. Bent on “doing as little as possible, for the shortest time possible, in return for as much money as possible,” their selfishness kept France from having enough weapons. Workers’ activism also won them shorter workdays and a share of the influence that had once belonged to the middle class. The middle class resented the workers’ gains. When the left won power in 1936, middle class morale plunged, and the many political leaders and politicians who came from this class developed poisonous attitudes against much of the country.

3. Pacifists: Pacifists preferred pursuing their dreams to national defense. They spewed falsehoods: that France’s economic system was too unjust to be worth fighting for, that the war’s inevitable destruction would achieve nothing, that the war would benefit only the rich, that France had caused the war, that the evils of Adolf Hitler were exaggerated. Their “somewhat sheep-like disciples” feasted on their words because they appealed to their “lazy, selfish instincts” and thereby became “a race of cowards.”

4. Minds: The French did not wield intellect as a weapon. “As a nation,” wrote Bloch, “we had been content with incomplete knowledge and imperfectly thought-out ideas.” Both suppliers and consumers of information were at fault. Newspapers often were secretly fronts for corrupt special interests, libraries did not stock enough serious books, officials failed to provide propaganda that would diminish the appeal of communism, an ideology that threatened morale, and schools produced stunted graduates who could not explain the deep historical roots of the present and had little desire to keep learning after graduation. Meanwhile, the French devoted little time to reading, were in thrall to the ideas of Karl Marx, and were blind to their contradictory desires to simultaneously extend both the sword and the olive branch toward Germany.

5. Leadership: Civilian leaders failed. Universities favored outmoded ideas. The “system” was corrupt. Officials underpaid teachers, and the wealthy paid bribes to plant articles or publish books favorable to their point of view. Politicians failed to ensure that France was ready for war but devoted significant energy to promoting particular individuals’ quest for power. By the time the war began, many French leaders hated what their country had become, so “they were ready to find consolation in the thought that beneath the ruins of France a shameful régime might be crushed to death, and that if they yielded it was to a punishment meted out by Destiny to a guilty nation.” Such people were not averse to a quick capitulation.

6. “The generation to which I belong”: Bloch made his analysis personal by implicating academics, which included himself. Although they recognized France’s problems, from disastrous foreign policy to aged leaders, they were too fearful, distracted by their work, and pessimistic about the difference they could make to speak up.