Why You Should Read In Search of the Promised Land

During the nineteenth century, the United States expanded like a hungry man’s waistline at Thanksgiving dinner, growing from sixteen states and 5.3 million people to forty-five states and a population of almost 76 million. But, like a man who has eaten far too much, it almost burst in two halfway through the gorging.

Living through all this transformation and crisis were multiple generations of the Thomases and Rapiers, an African-American extended family. By hard work, resourcefulness, courage, and good connections, they made an extraordinarily rapid rise, winning not only freedom from slavery but even positions of power and wealth. In Search of the Promised Land: A Slave Family in the Old South by Loren Schweninger and John Hope Franklin recounts their story. For making the histories of slavery, national expansion, Civil War, and Reconstruction come alive by showing through novelistic writing how they played out in the life of one family, In Search of the Promised Land is a book you should read.

Sally Thomas, the family matriarch, helped to provide her descendants with a better future but never enjoyed as much freedom as they did. Born into slavery in Albemarle County, Virginia, in 1787, she gave birth to John in 1808 and Henry in 1809. A white man, most likely the brother of Sally’s owner, fathered both. According to the authors, it is unknown whether she “suffered or accepted his sexual advances.” In 1817, after their owner died, Sally and her children passed to an heir in Nashville, Tennessee. The heir took little interest in them, so they gained a rare status by becoming what were called “quasi-slaves,” people who continued to be owned by another and sometimes had to pay their masters some of their income but were otherwise free to run their own lives. Sally used her limited liberty to start a laundry business. In 1827, she became mother to a third son, James, also fathered by a white man, this time Tennessee Supreme Court judge John Catron, who took no responsibility for the child. Sally devoted herself to improving her sons’ lives. She also eventually bought her own freedom by borrowing money and then paying back the lender. But Tennessee law rendered this an incomplete achievement – even after Sally paid off the debt. Slaves who bought their freedom remained technically the property of their owners unless county officials approved their freedom. Sally apparently did not seek government sanction for her freedom, maybe because after being legally freed from bondage slaves had to leave Tennessee unless they paid what was called a “good behavior bond” and won an exemption from county officials.

Sally found John a job working on a riverboat for Richard Rapier. John’s future brightened under Rapier’s employment. At a time when laws in much of the South forbade slaves to learn to read and write, John obtained these skills, and Rapier left in his will that he wanted his estate to buy John out of slavery. The executors not only complied but in 1829 convinced the State of Alabama, where John was then living, to give him a free man’s legal status. In Alabama, John became a barber, married, and between 1831 and 1837 fathered four free sons. After his wife died in 1841, he married an enslaved woman and had five children with her. Partly out of concern for the poor prospects for these children, who received their mother’s status as slaves, he mulled leaving Alabama but struggled to come up with a better place to go.

Henry Thomas took a more perilous road to freedom. In 1834, when a new owner inherited the family, Sally feared for his future and counseled him to run. Henry made it to Buffalo, New York, where he married, found work as a barber, and joined the movement for racial equality. But in 1850 the prospect that his past could devour everything he had achieved began to loom over his life when Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it easier to recapture runaway slaves. The following year he took his family into Canada.

John’s children spread across the country, and most achieved success. After his wife died in 1841, John sent Richard to live with his uncle Henry. There, he received an education, and in 1850 he joined the wave of Americans seeking gold in the newly acquired territory of California. His troubled brother Henry Rapier also headed there, but he took up gambling, and his life fell apart. Meanwhile, Sally took in John’s other sons: John Rapier, Jr., and James Thomas Rapier. In Nashville, both learned to read. In search of land in 1856, John joined his uncle James on a journey to Nicaragua, where Nashville resident William Walker had recently overthrown the government. Soon after arrival, the two concluded that this was headed nowhere good and got out. John spent the next few years in Minnesota Territory then turned sharply south and spent the early 1860s in Haiti and Jamaica, where he started studying medicine. He eventually finished his degree in Iowa in 1864. In 1856, James Thomas Rapier joined his uncle Henry in Canada. There, he had an Evangelical conversion experience, finished his education, and became a teacher.

The Civil War and the abolition of slavery opened new opportunities for the family. John Rapier, Jr., became an Army surgeon. After the war, his father helped to register voters in Alabama. James Thomas Rapier and his uncle Henry both returned to the South and entered politics.

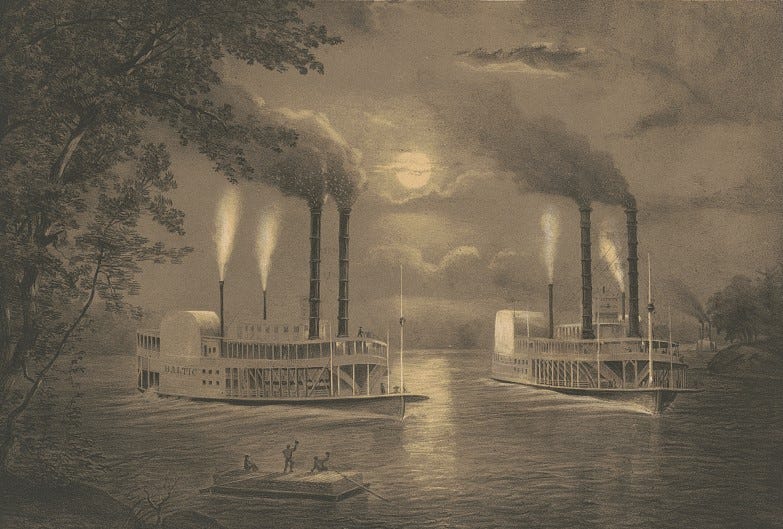

None of Sally’s children rose higher than James. Sally provided him with an education, sent him to New Orleans to broaden his horizons, and got him a job as a dental assistant. In 1834, she borrowed money from lawyer and planter Ephraim H. Foster to buy James’s freedom. James became a barber’s apprentice in 1841. Five years later, he opened his own barbershop, where he soon earned so much that he was able to start investing in real estate. He toured the North as the servant of planter Andrew Jackson Polk in 1848 and 1851. In 1851, Foster again intervened in James’s life by successfully arguing before officials from Davidson County, Tennessee, that James ought to be legally freed and by paying his bond. James then was able to convince the officials to let him stay in the state. But that was a high point of James’s life in Tennessee. During the 1850s, as conflict between North and South over slavery intensified, Tennessee law and its enforcement grew even more repressive toward African Americans. These obstacles drove James to join his nephew on their ill-fated trip to Nicaragua and later to move to Kansas, which had just been opened to settlement. Finding the state riven by conflict over slavery, he began working as a barber on a Mississippi River steamboat. He spent the Civil War years barbering in St. Louis, where he briefly considered siding with the Confederacy and encountered Ulysses S. Grant. In 1868, he married Antoinette Rutgers, a black woman who owned a fortune in real estate. Thomas had reached his peak. By 1870, only two Southern black families were richer than the Thomases, and James could afford a trip to Europe in which he saw “thirty-two cities in six countries in three months” and had his bust sculpted in Rome. But then his fortunes suffered a terrible fall.

Franklin and Schweninger admitted that the Thomases and Rapiers were hardly typical. Few slaves held Sally’s quasi-slave status, and her descendants were helped by their biracial ancestry. Before the abolition of slavery, people of mixed ancestry typically had more opportunities than those of fully African ancestry. In Search of the Promised Land is not a helpful source on the typical experience of enslaved African Americans. But, as the authors also pointed out, the unique status of the Thomases and Rapiers allowed them to leave behind something rare: detailed, African-American perspectives on a wide-range of nineteenth-century life. The family’s history is also a captivating story, a real-life epic.