Why You Should Read The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin participated in writing the Declaration of Independence, negotiating an alliance between France and the United States during the American Revolution, and creating the United States Constitution – but none of that comes into his autobiography. Instead, Franklin’s autobiography focuses entirely on his life up to 1760, when Franklin was in his mid-fifties, long before the American Revolution. But even though it leaves out much of what Franklin is most famous for, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin is still a book you should read. Franklin was a significant person long before the Revolution, and his autobiography is a good introduction to him. It also offers a compelling story, a vivid glimpse at life in the American colonies, and even some wisdom.

Franklin engineered a remarkable ascent. Born in Boston in 1706, the fifteenth of his father’s seventeen children, he was formally educated only to the age of ten because his vast numbers of siblings consumed the money that might have put Franklin through college and because Franklin’s father observed that a college education often did not lead to lucrative work. But although Franklin’s education ended early, he developed himself by extensive reading and by practicing his writing. His working years began in his father’s store and candlemaking business. Then, at age twelve, he became an apprentice for his brother, a printer.

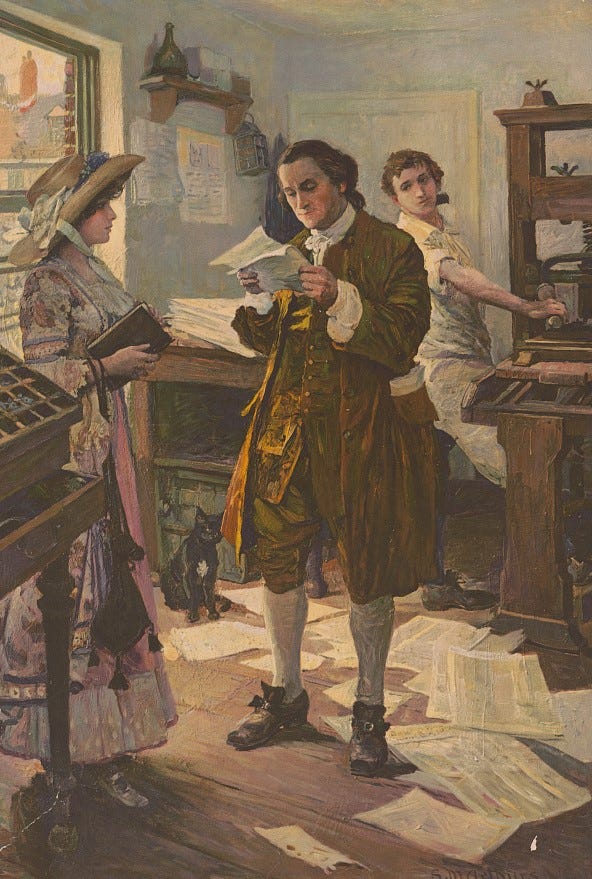

Franklin began a new era of independent living when he fled from his brother to Philadelphia in 1723. On his own, printing continued to sustain him. He worked as a printer in Philadelphia and between 1724 and 1726, when he lived in London. Back in Philadelphia in 1727, he and a partner founded their own print shop, and within a few years Franklin became its sole proprietor. His business flourished. He broadened it into publishing a newspaper and selling paper and notebooks and won plum contracts, such as the Pennsylvania legislature’s printing. For decades, starting in the 1730s, he wrote Poor Richard’s Almanac. Around 1750, Franklin had become so successful that he left the running of his print shop to a partner and retired to live on the profits “as a man of leisure” who devoted his time to public service and study, including electricity.

Franklin’s autobiography is a source not only for studying Franklin’s life but also American colonial history. Smallpox, a disease that scourged the colonies, also touched Franklin’s life, killing one of his children at the age of four, and he urged readers to have their children inoculated against it. He observed the Quakers, Pennsylvania’s most influential denomination in the first half of the eighteenth century. He attended at least one of their meetings and recorded their struggle with the tension between the colony’s need for defense and their doctrine of pacifism. He participated in the conflict between the Pennsylvania assembly and the colony’s proprietors, the descendants of William Penn, to whom the colony had been granted in the late seventeenth century. The assembly wanted the proprietors’ land to be fair game when it taxed the colony to raise money for defense, but the proprietors feared that their inclusion in such measures would rob them, and they resisted by having the governor veto every tax bill. In the course of this conflict, Franklin had a portentous exchange with Lord Granville, the head of the king’s Privy Council. Granville said the colonists had to obey the king’s will. Franklin believed that the colonies’ charters gave their representative assemblies the right to participate in their government so that “as the Assemblies could not make permanent laws without his assent, so neither could he make a law for them without theirs.” He met Gen. Edward Braddock, who was leading an expedition of British and American soldiers against a strategically located French fort in western Pennsylvania in 1755. In addition to helping to supply Braddock, Franklin warned him that there were likely to be ambushes. Braddock replied, “These savages may, indeed, be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia, but upon the king’s regular and disciplin’d troops, sir, it is impossible that they should make any impression” – then led his forces into a French and Indian buzzsaw that routed them.

Franklin sparred with but respected the dynamic Great Awakening preacher George Whitefield. As a young man, Franklin parted from his parents’ Reformed Protestant faith, concluding that salvation came by good works, not Christ, that God did not intervene in His creation, and that human nature is not totally enslaved to sin – ideas that directly countered Whitefield’s theology. Nevertheless, he printed Whitefield’s sermons and other writings and appreciated Whitefield’s ability as a speaker. He estimated that Whitefield’s voice could reach a crowd of 30,000. He also found Whitefield persuasive. On one occasion, he had resolved not to donate to Whitefield, but he went against his impulse after hearing Whitefield speak. But, unlike many others, Franklin was unmoved by Whitefield’s presentation of the gospel. Franklin recalled that Whitefield would “pray for my conversion, but never had the satisfaction of believing that his prayers were heard.”

Franklin was a bit conceited, but his autobiography still has some wisdom to offer. That means he at least partly achieved one of his goals for it: to pass on “the conducing means I made use of” to achieve wealth, fame, and happiness. As a young man he learned that he could discuss weighty matters more effectively if he made his points in a way that suggested that he might be wrong, by, for example, using the phrase “it appears to me.” This approach made others more willing to listen and to correct him. Franklin’s community-oriented life contrasted starkly with the loneliness of the twenty-first century. In Philadelphia, he helped to found an intellectual discussion club, a subscription library, a firefighting company that met once a month to discuss fire safety, a paupers’ hospital, and a school that became the University of Pennsylvania, and he helped to reform the night watch. When French attack threatened Pennsylvania in the 1740s, he helped to build up the colony’s defenses. He modeled a commitment to reading and the difference it can make. In his twenties, he read for an hour or two per day for his own “improvement.”

Franklin was devoted to self-improvement, so his realization of the limits of his power to develop his virtue is maybe his most significant lesson. As a young man, Franklin tried to achieve “moral perfection. I wish’d to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into. As I knew, or thought I knew, what was right and wrong, I did not see why I might not always do the one and avoid the other.” He was mistaken. “I soon found I had undertaken a task of more difficulty than I had imagined,” he recalled. “While my care was employ’d in guarding against one fault, I was often surprised by another; habit took the advantage of inattention; inclination was sometimes too strong for reason.” Trying a new method, he listed thirteen virtues, such as “silence,” “order,” “frugality,” and “industry” and came up with a program to encourage them. While this new approach improved his character, Franklin still “fell far short of” achieving “perfection.” For one thing, all Franklin’s virtues involved “good works” rather than the heart, and Franklin eventually recognized that his inner character could lag behind his outward appearance. He tried to tackle pride by blunting his words, but, though this may have allowed him to go fifty years without uttering “a dogmatical expression,” inside he remained puffed up. He concluded that pride might be the hardest fault to stamp out. He predicted that if he ever thought thought he had eliminated it “I should probably be proud of my humility.”