The Stormy Lame-Duck Period

I was born – but pretty out of it – for the Election of 1988. The first presidential election I remember is the election of 1992. In the days after the election, I was surprised to find out that George Bush was still president and would remain in office for several months even though he lost.

It was my introduction to the lame-duck period, the months between Election Day and Inauguration Day when the current president has been voted out, decided not to run again, or reached the term limit. More than two months is a long time for the president to be partly hamstrung and partly empowered by being on the way out, but the lame-duck period used to be longer. From 1793 to 1933, presidents were inaugurated on March 4. The Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in February 1933, moved Inauguration Day up to January 20 beginning in 1937. By often using the beginning and end of presidential administrations to periodize the past, historians create the false impression that nothing happens during the lame-duck period. But because of how consequential presidential elections are – and because of how insignificant they are in the face of events that have their own momentum – the lame-duck period has often been a time of great crisis or significant change.

Sometimes, the lame-duck period has been shortened or tense because the winner of the election is still being determined – or the result is being contested. This was the case during the 1800-1801, 1824-1825, 1876-1877, 2000-2001, and 2020-2021 lame-duck periods.

The 1848-1849 lame-duck period came at the beginning of the California Gold Rush. In 1846, President James K. Polk had taken the United States to war with Mexico. The peace treaty, signed on February 2, 1848, delivered California to the United States. What the signers did not know was that gold had been discovered in California a week before. It soon touched off a rush to California from the closest places: Mexico, Hawaii, and far western North America. Polk decided not to run for reelection in 1848. It would be more than a decade until the new technology of the telegraph provided instant communication between the Western and Eastern United States, so it took a long time for word of the gold to reach the East. It was during the lame-duck period that word of gold began to spread widely. Polk announced it in his Annual Message to Congress, delivered on December 5. Two days later, $4,000 in gold arrived from California. The secretary of war announced that he would have it turned into medals for veterans of the Mexican-American War. The publicity created by these events inspired tens of thousands of people from the Eastern United States to head for California in 1849.

The lame-duck period has come during domestic crisis. During the 2008-2009 lame-duck period, it was the Great Recession. The stock market fell by 17 percent between Election Day and Inauguration Day, having already crashed by more than a quarter in the months before the election. Between Election Day 2020 and Inauguration Day 2021, more than 200,000 Americans died of pandemic coronavirus – almost as many as had died in the previous eleven months.

The lame-duck period has come in the midst of military or diplomatic crisis. Sometimes these crises have ground on into the term of the incoming president. The lame-duck periods of 1952-1953 and 1968-1969 were blips in the much longer span of the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Other times, the lame-duck period has come near the end of these crises. During the 1980-1981 lame-duck period, fifty-two of the sixty-six people who had been taken hostage at the American embassy in Tehran, Iran, in November 1979 remained in captivity. They went free just hours after the end of outgoing President Jimmy Carter’s lame-duck period on January 20, 1981. By the Election of 1876, the United States was fighting a war it had provoked with Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne Indians. The summer before the election, warriors from these tribes killed Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and much of his Seventh Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. During the 1876-1877 lame duck period, American forces in Montana and Wyoming conducted several successful raids against these tribes that played significant roles in helping the United States to win the war by mid-1877 and thereby claim the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota and large parts of what are now Wyoming and Montana.

Presidential activity has made the lame-duck period a significant time. On March 1, 1845, President John Tyler signed a bill to annex Texas. In 1961, with three days remaining in his presidency, Dwight Eisenhower addressed the nation on several threats to liberty: excessive federal influence on scientific and technological research, excessive influence by scientists and engineers on the federal government, and, at a time of high defense spending on the Cold War, “the acquisition of unwarranted influence . . . by the military-industrial complex” – the officials buying defense equipment and the businesses making it.[1]

During the 1801 lame-duck period, President John Adams appointed a host of judges – often referred to as “midnight judges” – from his Federalist Party before power passed to Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson.[2] One was John Marshall, the most significant chief justice in the court’s history. Another was William Marbury. Marbury did not receive his written commission before Adams’s term ended. Once he came to power, Jefferson refused to give it to him. Marbury sued. In 1803, Marshall wrote the decision determining Marbury’s fate, ruling in the case of Marbury vs. Madison that Marbury should not be granted his commission because the 1789 law that would have allowed the court to force the delivery of his commission was unconstitutional. Thus a lame-duck appointee opened the door for the first use of judicial review to strike down a law as unconstitutional in American history.

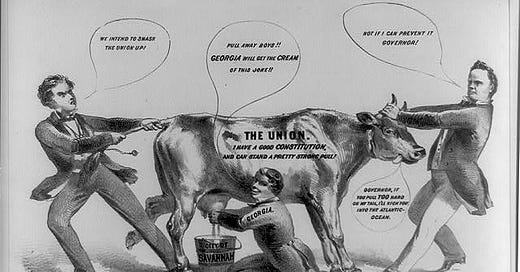

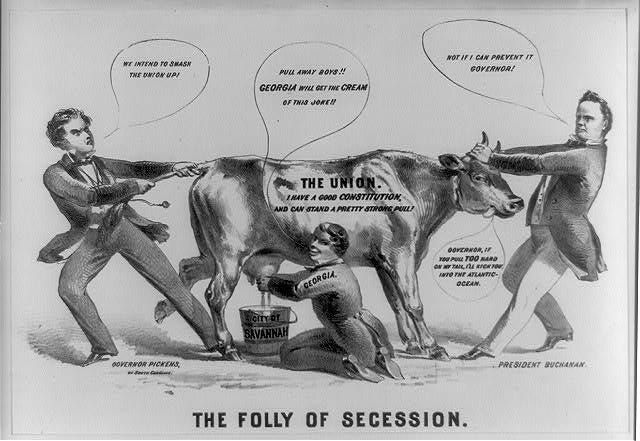

Two lame-duck periods stand out above them all. One followed the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In response, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas left the Union, wrote a constitution, chose Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis as their president, and took control of the arsenals, mint, and post offices in these states by Inauguration Day. The hostility to Lincoln was so great in the slave state of Maryland that he had to be smuggled into Washington, D.C., in the dead of night to reach the capital by Inauguration Day.

The other was the lame-duck period of 1932-1933, the last of the four-month lame-duck periods. In the final four months of ousted president Herbert Hoover, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Japan left the League of Nations. The United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. Unemployment was about 20 percent. Large numbers of banks collapsed. Just before Inauguration Day, the number of Americans pulling their savings out of banks spiked, so state governments closed most or all of their banks or at least limited the amount that depositors could withdraw. And the president-elect almost didn’t make it to Inauguration Day. On February 15, while Franklin Roosevelt was visiting Miami, an assassin fired at him. He missed, but he did hit Chicago mayor Anton Cermak, who died of his wounds a few weeks later. One of Roosevelt’s aides captured the wild possibilities of the lame-duck period when he wrote, shortly after the Election of 1932, “by March 4 next we may have anything on our hands from a recovery to a revolution. The chance is about even either way.”[3]

Article Recommendations

Political scientist Ryan Burge on the extent of religious influence on Republicans.

I wrote last week about how various demographics voted. Here’s another look at the demographics of 2024.

Historian Thomas Kidd on how he avoids getting preoccupied with the news.

Another reason to doubt the value of today’s college degrees: This article examines the pandemic of student cheating.

The reporter drew heavily on an interview with University of Louisville professor Amy Clukey. “ ‘I was just hit,’ [Clukey] said, ‘by a student army of cheating.’ Students cheated on informal discussion-board prompts. They cheated on essays. A few weeks ago, she emailed a student to say that she knew the student had cheated on a minor assignment with AI and if she did it again, she would fail the course. Clukey also noted there were several missed assignments. The student replied to ‘sincerely apologize,’ said she was ‘committed to getting back on track,’ and that she regretted ‘any disruption [her] absence or incomplete work may have caused in the course.’ But her next paper was essentially written by artificial intelligence. Curious, Clukey asked ChatGPT to write an email apologizing to a professor for plagiarism and missed work.

“ ‘And what did it do?’ she said. ‘It spit out an email almost exactly like the one I had gotten.’ ”

Peggy Noonan captured the state of the United States well in her post-election column. She wrote, “when a single candidate increases his totals in almost every group but one, white women, something big happened.”

Recent years were nationally humiliating, and the failures were not only on the news. Bad policy affected me personally. I loathed having to wear a mask to teach, go to church, or shop and enduring diversity training and other forms of cultural revolution at my university. Noonan’s description of this dreadful era resonated with me: “The people did what they wished. They revolted. They looked at the past four years of Washington and said no. They said ‘Goodbye to all that,’ to the years 2020-24 – to the pandemic, to the pain and damage of that era, which affected every part of our lives. That is the real turning of the page I think, from a time they hated that made them view their government as bullying and not that bright. In terms of issues it was illegal immigration, inflation and a rejection of the deterioration all around them – of drugstores locking up the shampoo and the beleaguered Walgreens employee late with the key to the cabinet and in a bad mood because he’s afraid of thieves and crazy people and it’s wearing him down. It was the woke regime, which people have come to experience as an invading force in their lives. It was Afghanistan, and other wars, and the sense Washington isn’t getting foreign policy right and perhaps barely thinking about it.”

Trump, by contrast stood for “exuberance, expansion, Musk to Mars, drill, baby, drill” – but he is likely to shoot himself in the foot. Noonan also wrote, “I don’t like the SOB, I think him a bad man who’ll cause and bungle crises almost from day one.”

[1] Jim Newton, Eisenhower: The White House Years (New York: Doubleday, 2011), 346.

[2] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 419.

[3] David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 117.